As the cold weather approaches and we are all spending more of our days indoors. The air we breathe or our indoor air quality (IAQ) becomes that much more important. We are continuing our series on Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) or by its latest name “Indoor Environmental Quality” (IEQ). It may sound like a bold statement but indoor relative humidity is the single biggest factor in IAQ. Its estimated that poor indoor air quality causes 20 million deaths annually around the world. Your home’s air can either bolster your health or actually make you sicker! We will be looking at work and studies carried out by Dr. Stephanie Taylor, an infectious disease control consultant at Harvard medical school.

“Relative humidity of 40-60% in buildings will reduce respiratory infections and save lives.“

Dr. Taylor and her team are canvassing the WHO to change their recommendations for relative humidity in occupied spaces. Dr. Taylor’s research presents evidence to support a range of 40%-60% indoor relative humidity levels and they make the following claims:

-

- Respiratory infections from seasonal respiratory viruses, such as flu, being significantly reduced.

-

- Thousands of lives saved every year from the reduction in seasonal respiratory illnesses.

-

- Global healthcare services being less burdened every winter.

-

- The world’s economies massively benefiting from less absenteeism.

-

- A healthier indoor environment and improved health for millions of people.

Taylor’s research is largely in public health and makes recommendations for Hospitals, schools, and offices but the studies apply equally to homes and perhaps more so as we spend more time at home than in the office.

In Canadian winters, most homes leak a significant amount of air through walls and windows. Without actively humidifying indoor air, the very dry outdoor air will reduce our indoor relative humidity to approx. 20%. This is far below the 40% minimum recommended by Dr. Taylor’s team. Let’s look at the reasons why 40%-60% is recommended zone for relative humidity.

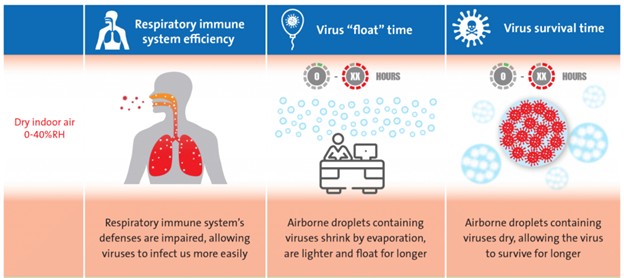

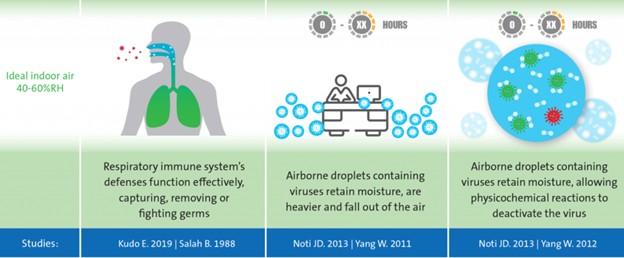

First, research has confirmed that in very dry conditions the immune system is suppressed and we grow more susceptible to infection.

Secondly, in dry air virus particles will aerosolize or go into suspension and stay suspended in the air more readily.

Thirdly the virus particles will go further and survive longer, meaning they can be circulating around your home!

This combination of factors in dry conditions dramatically increases infection rates from viruses.

Conversely, with relative humidity in the 40%-60% range, the immune system’s defenses are bolstered and function more effectively. The virus float time or the time spent suspended in the air is reduced and the increased moisture (humidity) helps to deactivate the virus.

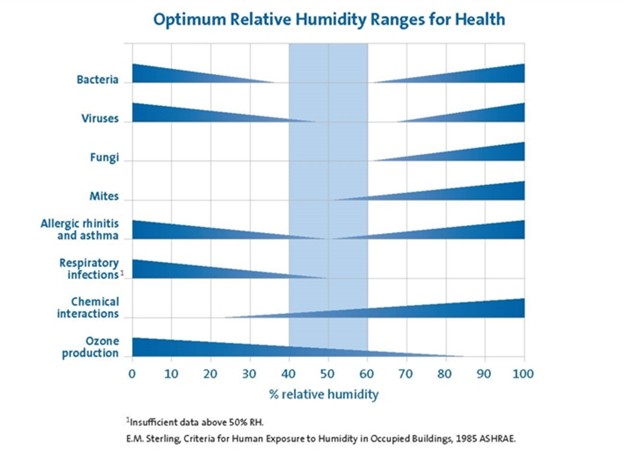

Like much of the building science we use today this 40-60% “sweet spot” of relative humidity was recognized in large part, back in the 1980s. This has become increasingly important as building envelopes tighten up and we spend more time indoors. The “Sterling Chart” shown below, from 1985 recommended 40-60% relative humidity as the zone of optimum health.

After the energy crisis of the 1970s, buildings were somewhat indiscriminately “sealed up” in an attempt to save energy with in some cases disastrous consequences. What was known as SBS “Sick Building Syndrome” drew much attention and research as people were experiencing adverse effects from their time spent at work in dry building conditions with polluted indoor air, caused in part by this “sealing up” of buildings. Elia Sterling’s research resulted in the Sterling Chart which is recognized widely by high performance building scientists and engineers as the “playbook” for the indoor environment.

OK……So let’s simply set our humidifiers to 50% and the problem is solved!

Building codes are quite slow-moving and typically follow technology and research developments. Codes represent minimum standards that are acceptable but by no means prescribe optimal requirements. A high performance home that optimizes health needs to be designed as a “system”. If our goal is to have 50% relative humidity to maximize health then we need to consider what other areas of the home are affected when we make changes? The home has now become a delicately engineered system which needs all the component parts coordinated.

Indoor Air Quality, Windows and Condensation

On cold mornings in Canada, when we turn up the humidity, the first and more obvious problem that presents itself is windows. At 50% Humidity most windows will likely be ringing wet with condensation spilling onto the window sills. This phenomenon of condensation, which can be plainly seen on the windows can also manifest itself in other areas, that aren’t so obvious. When any surface is colder than the air’s saturation point, just like a cold pop can on a hot day, condensation will form on it. Read more about energy efficient windows.https://chatsworthfinehomes.com/choosing-energy-efficient-windows/

It could be in a crawl space or behind cupboards. Condensation can foster mold growth! Then by alleviating one problem ( low humidity) we can create another ( mold). Similarly, where cold outside air rushes into the home, cold spots can result and condensation can occur. And those spots often are not visible and can result in mold growth.

These unintended consequences ( mold) can occur when a home isn’t carefully and holistically designed. One “solution” can create another problem. By designing a high-performance home with carefully considered building science precisely applied to All components of the home, the result is a “biodome” to nurture and optimize your family’s health. That’s great IAQ and a healthy family!

Additional Resources

Seasonality of Respiratory Viral Infections – Moriyama et at 2020

2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic: Built Environment Considerations To Reduce Transmission – Dietz et al 2020

Low ambient humidity impairs barrier function and innate resistance against influenza infection – Kudo et al 2019

High Humidity Leads to Loss of Infectious Influenza Virus from Simulated Coughs – Noti et al 2013

Indirect health effects of relative humidity in indoor environments – Arundel et al 1986

Relationship between Humidity and Influenza A Viability in Droplets and Implications for Influenza’s Seasonality – Yang et al 20